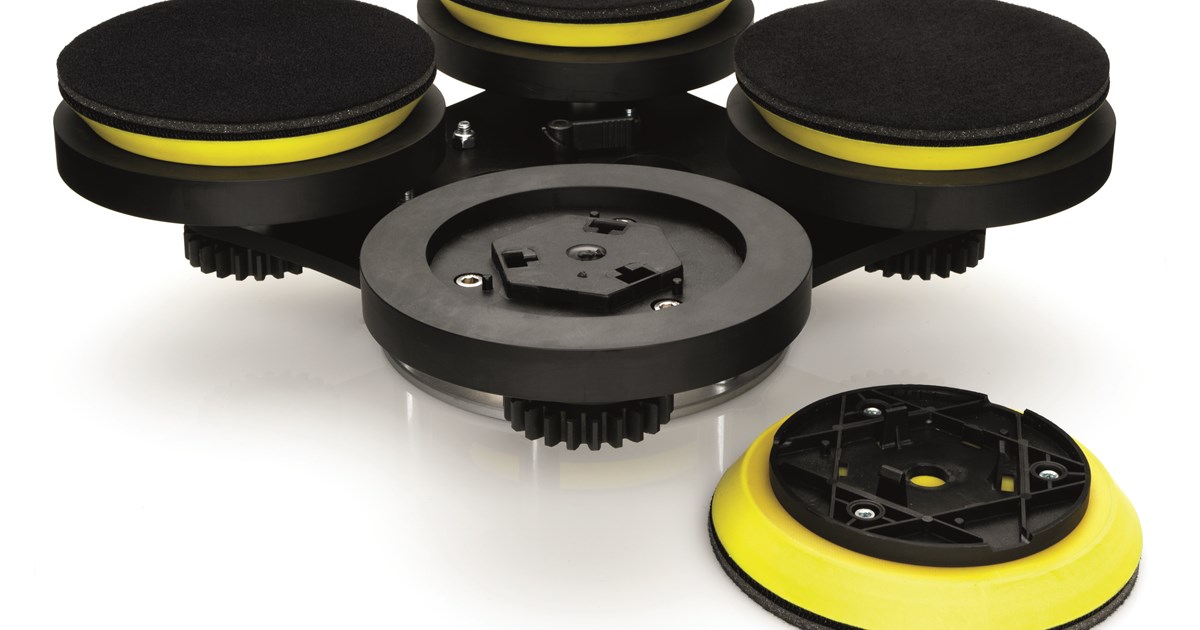

Bona FlexiSand 1.5 Power Drive Pro System,Wood Flooring Sanding Machine Review, Floor Sanding Machinery from Bona

Bona Power Drive Weight Kit (Predrilled Chassis) - Floor Mechanics - The World's Fastest Free Delivery For Hardwood Flooring Contractors. Huge Inventory, Same Day Shipping.